Battling an Eating Disorder at a Young Age

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) may not come to mind when you think of eating disorders. Also known as ARFID, it’s defined as a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs. It leads to weight loss or inadequate growth, nutritional deficiency, and/or the need to take supplements in order to get enough calories and nutrients. It is quite different from other eating disorders in that it is not body image based and there is no fear of weight gain.

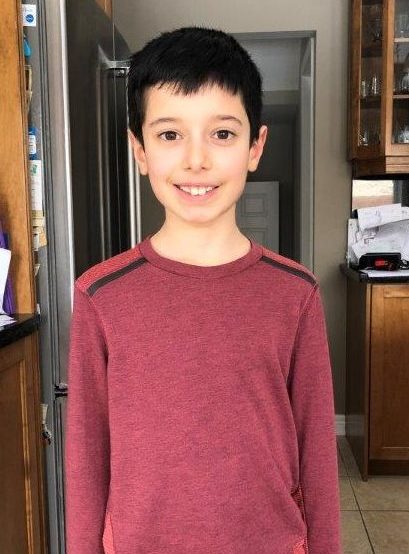

Parents, Orietta and Mark, first noticed symptoms when their son, Eric, was only 6 months old and starting to try solid foods. Eric would reject all foods and even vomit, while his twin brother Adam, couldn’t get enough of food. Eric’s parents were desperate for help, as Eric lost weight and continued to fall off his growth curve.

Desperate for help

It is difficult to diagnose ARFID. Eric’s doctor recommended that he stay on formula until the age of 2, and drink Pediasure as he grew older, to meet his nutritional requirements. As he grew, his solid food diet consisted of only a few dry foods like crackers and chips. This was immensely challenging for his family.

“As Italians, food is such a big part of life,” says Eric’s mom, Orietta. “It is considered one of life’s greatest pleasures.”

“Sometimes I would have to tell the other kids that Eric has a ‘different tummy’”

It became stressful to plan outings and go to birthday parties, knowing Eric would only eat a select few things. Sometimes his parents would have to feed him what he liked before going anywhere, which meant a lot of regimented planning. Eric’s mother, Orietta adds, “Sometimes I would have to tell the other kids that Eric has a ‘different tummy’ to explain to them why he wasn’t eating.”

Eric’s parents emphasize that they were lucky that Eric’s friends, family, and school were all very understanding and supportive. Still, Eric would sometimes wonder, “Why me?” which left his parents heartbroken.

Finding answers

Eric’s mother, Orietta, grew frustrated and did a lot of research. She found a connection between occupational therapists and eating disorders, and were referred to one at Hamilton Health Sciences’ former Chedoke Hospital, whose services are now housed at Ron Joyce Children’s Health Centre.

Part of their treatment involved food therapy, which included the simple act of just touching different foods with different textures. This would help to alleviate some of that fear associated with even the idea of different foods.

When Eric turned 7, the doctors determined he had reached a roadblock and referred him to McMaster Children’s Hospital for more intensive treatment. Weekly appointments with Kyrsten Doxtdator, a social worker in the Eating Disorders Clinic, and Dr. Natasha Johnson, an eating disorder specialist, helped Eric make further progress. And it was a chance for him and his Dad, Mark, to bond.

Kyrsten came up with strategies to help Eric essentially re-train his mind to accept new and different foods. Eric’s Dad recalls, “a lot of negotiation took place, it was funny to see their back-and-forth.”

They came up with best and worst case scenarios to help him understand his anxiety, and develop more rational thought patterns. This is part of a treatment called Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT).

They also used exposure therapy. “We created exposure hierarchies, where we’d construct a list of foods Eric would like to eat, rating them on a scale from 0 – 10″, says Kyrsten. “Then Eric would be tasked with trying these foods at home, while his parents would be tasked with portioning these foods in order to help him to get to a healthier weight.”

Following the patient’s lead

It was important that Eric accepted and agreed to the plan. He would leave his session with a list of things he agreed to do and eat. When he returned for his next appointment having accomplished his goal, he would be rewarded with stickers, which he would collect to earn a prize. As many parents know, negotiating with your kids can be stressful, and positive reinforcement can be very effective.

“It’s important to challenge him, but at the same time you need to respect his tolerance”

Kyrsten also emphasized the importance of respecting Eric’s boundaries. “It’s important to challenge him, but at the same time you need to respect his tolerance. If he is really getting upset over a certain food, drop it and try it another time,” she says.

Today, Eric has made great progress. His favourite foods include ribs, tacos, quesadillas and pizza from his parents’ outdoor wood burning oven. And he is no longer reliant on Pediasure for his growth and development. “He’ll always eat at least one thing from our family meal,” Eric’s dad, Mark, says. They keep his food chart up in his bedroom as motivation. It showcases all the different foods he’s tried and enjoyed.

Eating Disorders in Children and Youth

Eating disorders are complex mental illnesses that affect the body physically as well. Eating disorders affect people of all genders, ages, classes, abilities and ethnic backgrounds. It is important to remember that eating disorders are serious, biologically influenced illnesses–not personal choices. While they can have life-threatening complications, eating disorders are treatable.

Eating disorders in children and youth are especially concerning because their growing bodies need enough food. And they typically affect females ten times more than males. According to recent studies, prevalence of the most common eating disorders is 0.3-1% for anorexia nervosa and perhaps three times that for bulimia nervosa.

The McMaster Eating Disorders Program provides a comprehensive assessment for patients referred for an eating disorders assessment. The Program was established in 2001 and provides 3 levels of service (outpatients, day treatment, and inpatients) to children and youth in our community. The staff and physicians are leaders in Canada in the delivery of outpatient Family Based Treatment (FBT) for eating disorders.

If you believe you or your child is showing symptoms of an eating disorder, please speak with your primary care provider as soon as possible. They can help make a diagnosis and refer you to specialty services.