Historic time capsule uncovered at Chedoke Campus

A piece of Hamilton’s history

If you dig around the city of Hamilton, you’ll find little pieces of history hidden in all corners. But rarely do those pieces paint so perfect a picture of the past as the time capsule that was recently uncovered in the Wilcox Pavilion on Hamilton Health Sciences’ (HHS) former Chedoke Campus.

“We wanted to make sure that this important part of Hamilton’s history is well preserved.”

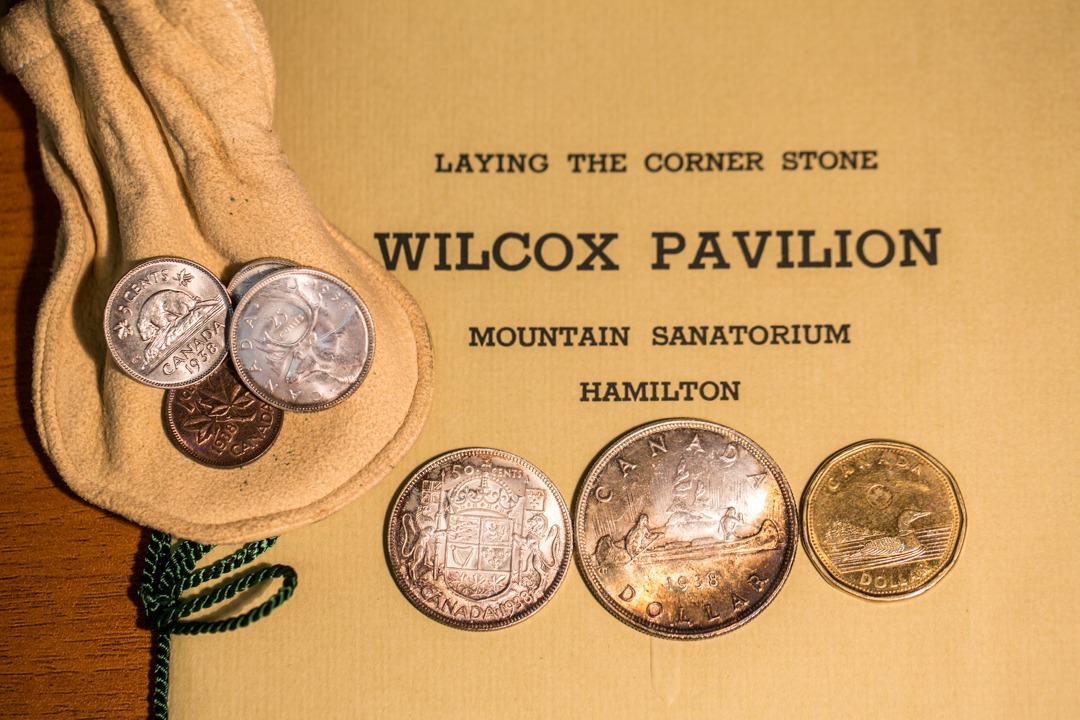

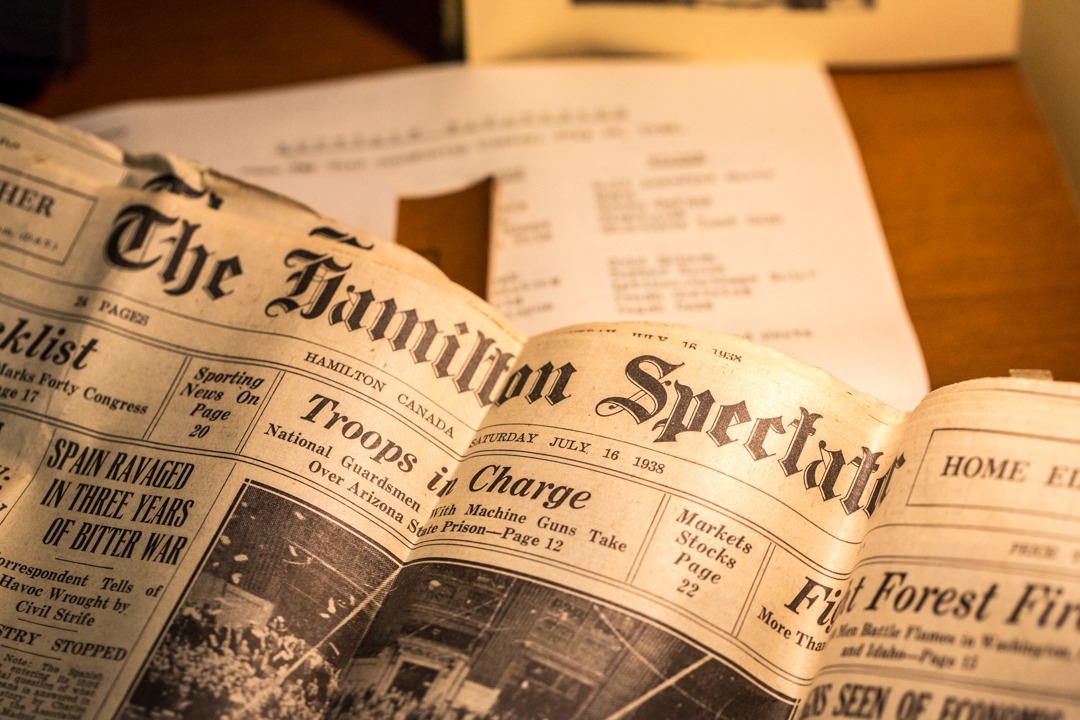

On July 18th, 1938, the turning of the sod marked the beginning of construction on the Wilcox Pavilion. It was built to meet growing demand for treatment at what was then called the Mountain Sanatorium, a tuberculosis hospital that housed hundreds of inpatients and staff on its grounds. A generous $250,000 donation by Charles Seward Wilcox, a member of the Sanatorium’s board of trustees, funded the project. At some point during construction, a sleek metal capsule was placed in the pavilion—a hidden look at life at the ‘San’ in 1938.

Preserving the contents of the capsule

The capsule was opened recently after the last HHS staff moved off the Chedoke Campus.

“We wanted to make sure that this important part of Hamilton’s history is well preserved,” says Kelly Campbell, vice president, corporate services & capital development at HHS. “When we moved out of the site, we uncovered the time capsule and donated its contents to the Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences at McMaster University.”

Buried when the cornerstone was laid, the capsule contained more than a dozen relics, ranging from the hospital’s 1938 budget to a time sheet scrawled with the names of two men who presumably worked on the building’s construction.

“Very few of these papers survived, but this gives us such a real look at what patients experienced.”

“It’s great to have a glimpse of what life was like for those patients and staff,” says Anne McKeage, a historian of health and medicine, who manages the Health Sciences Library’s archive. “We have hundreds of annual reports and official documents, but stuff like this doesn’t usually survive. And it’s this kind of ephemera, that came through peoples’ hands, that preserves what they were really doing, eating, and thinking.”

A looking glass into life at the ‘San’

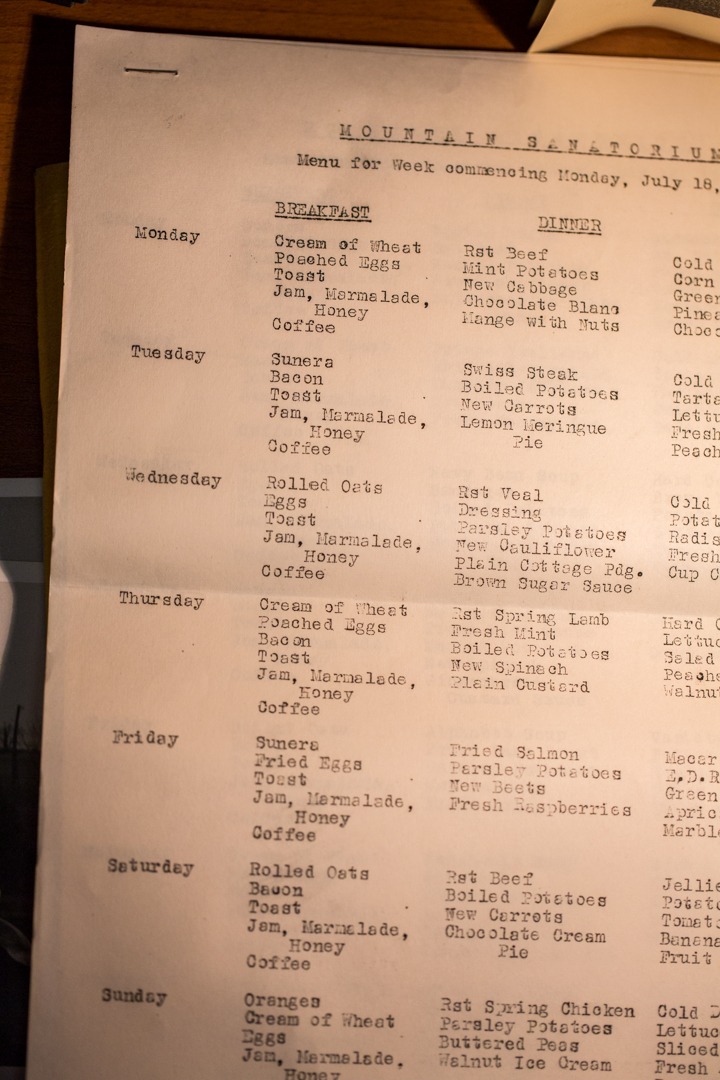

A few items in particular speak to life in the era, and the nature of care provided at the Sanatorium. A lengthy menu lists a week’s worth of food patients were invited to devour, including roast spring lamb, trout and walnut ice cream. Tuberculosis patients often lost a lot of weight from the illness and encouraging them to put on pounds was considered part of treatment.

The capsule also contained an issue of the ‘Santowner’, a patient-created newsletter featuring their own drawings, stories and poetry. It was a way for them to pass time while they were on bed rest. A particularly telling excerpt from the first page includes a welcome message with advice to newcomer patients, “DON’T REBEL! The sooner you adapt yourself, the quicker the cure will begin…BE ADAPTABLE, BE CHEERFUL, BE INTERESTED, and very soon we’ll be saying ‘Goodbye friend! It’s been grand knowing you.’”

“It’s really neat to see patient publications like this,” says McKeage. “Normally, you’d get one of these, read it, and throw it out. Very few of these papers survived, but this gives us such a real look at what patients experienced.”

What happened to the man that made it happen

Conspicuously missing from the capsule is a strong presence from the Pavilion’s benefactor, Charles Wilcox. He can be seen sitting in a car in one photograph, but is strangely absent from the ceremonial images of the sod-turning. Further investigation reveals that he was, in fact, quite ill when the project began, and died just six weeks before the product of his generous donation officially opened on January 7th, 1939.

His legacy provided 174 beds for tuberculosis patients, and formed an important part of Chedoke’s history that is now preserved for future generations to appreciate.