Recreation therapists help patients living with dementia feel seen, heard, valued

Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) patient Brent Alton doesn’t recall a lot about his former life as a police officer and security guard. But 89-year-old Brent, who lives with dementia, still fondly remembers his wife Marg and looks forward to her visits at HHS’ St. Peter’s Hospital, where he’s a patient in the behavioural health program.

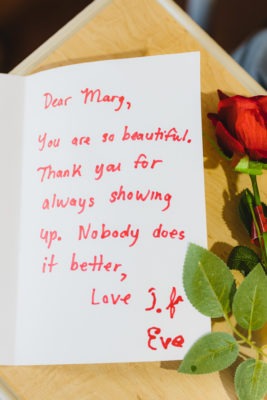

St. Peter’s Hospital patient Brent Alton surprises his wife Marg with a Valentine’s Day card that he made with help from one of the hospital’s recreation therapists.

The Altons are sharing their story this February for Recreational Therapy Month to highlight how recreation therapists help Brent, who was diagnosed with dementia four years ago.

Support helps prepare patients for discharge

The behavioural health program is a specialized service for adults who have been diagnosed with dementia and show responsive and/or reactive behaviours such as wandering, exit seeking, delusions, mood swings, agitation, and physical or emotional outbursts as a way of responding to something negative, frustrating or confusing in their lives.

Recreation therapist Niomi Dyon helped patient Brent Alton put his thoughts on paper for a touching Valentine’s Day card to his wife, Marg

“He’s still very confused, but his anxiety level is much lower since being admitted to St. Peter’s.” — Marg Alton, Brent’s wife

“When people living with dementia aren’t able to express their needs, this can translate into anger or frustration,” says Liz Mersereau, the program’s clinical manager. “The challenge for our team is to try and understand the meaning behind the behaviour, because if we understand why patients are responding or reacting in a particular way, we can help prevent it from happening again.”

Patients are assessed, treated and provided with support so they can be discharged to long-term care. This is typically accomplished through combination of medication and interventions including recreational therapy, which uses leisure and play to help reduce the intensity and frequency of behaviours that prevent patients from being discharged.

Understanding the patient

Recreational therapy activities are connected to the patient’s personal interests and meet their specific needs for movement, stimulation, relaxation, and social experiences.

The cover of Brent Alton’s homemade card to his wife Marg includes a photo of the couple

Brent was becoming increasingly agitated before being admitted to St. Peter’s Hospital last May. The combination of medication and specialized care including recreational therapy is working wonders in helping him become calmer. “He’s still very confused, but his anxiety level is much lower since being admitted to St. Peter’s,” says Marg.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, recreation therapists at St. Peter’s Hospital have been working one-on-one with patients. They conduct an intensive assessment to learn about the patient and develop programming based on the patient’s needs, interests, skills and abilities.

“We have specific goals for each patient depending on their profile, level of ability, and where they’re at in their disease progression,” says Mersereau. “Our recreation therapists play a key role in supporting these goals.”

Recreation therapists show a genuine interest in the patient and their history, and introduce meaningful activities into their day to help them feel understood and happy.

“We know that boredom, loneliness and social isolation are the main reasons why patients with dementia express themselves in certain ways,” says Naomi Dyon, a recreation therapist with the program. “We use leisure to help with this, so that our patients feel included, heard and valued. Our goal is to add meaning and purpose to their day, every day, and give them something to look forward to.”

Recreation therapists working with Brent at St. Peter’s Hospital include Crissie Leng and Naomi Dyon

Activities Brent took part in this month, with support from recreation therapists, included a Valentine’s Day card-making craft. Brent especially enjoyed writing a heartfelt message to his wife.

“He knows who Marg is and he adores her,” says Dyon. “He waits by the door for her visits. He really loves and appreciates his wife.”

Meaningful moments

The behavioural health team calls such activities “meaningful moments.”

Recreational therapists tap into patients’ interests in a number of ways.

For some patients, a meaningful moment might be enjoying a favourite hobby, like crocheting or listening to Dyon play guitar. Patients with more advanced dementia might find comfort in holding a sensory blanket. These blankets have objects like zippers and textured material that keep a patient’s hands busy to help relieve stress.

“A patient living with dementia may no longer have the capacity to enjoy, for example, a TV show,” says Mersereau. “But if we can provide meaningful moments throughout their day in a variety of ways, then we’ve added some quality to their life while they’re here with us.”

Brent doesn’t remember a great deal from his time as a police officer and security guard. But he remains protective of others, and has an innate interest in subjects relating to earlier aspects of his life.

His recreational therapists were able to tap into those interests in a number of ways. For example, Dyon made a booklet for Brent featuring celebrity mug shots, and encouraged him to match mug shots to celebrities’ photos. “He really found this activity satisfying,” says Dyon. “Working on this activity felt very purposeful to Brent because it tweaked some positive memories.”

The care Brent receives has been wonderful, adds Marg. “Compared to a year ago things are getting so much better.”