Taking technology for blood-clotting disorders to the next level

Deep curiosity combined with a passion for improving the lives of patients on blood thinners and with blood clotting disorders was the driving force behind finding the tools to identify the presence of blood thinners in individuals undergoing surgery.

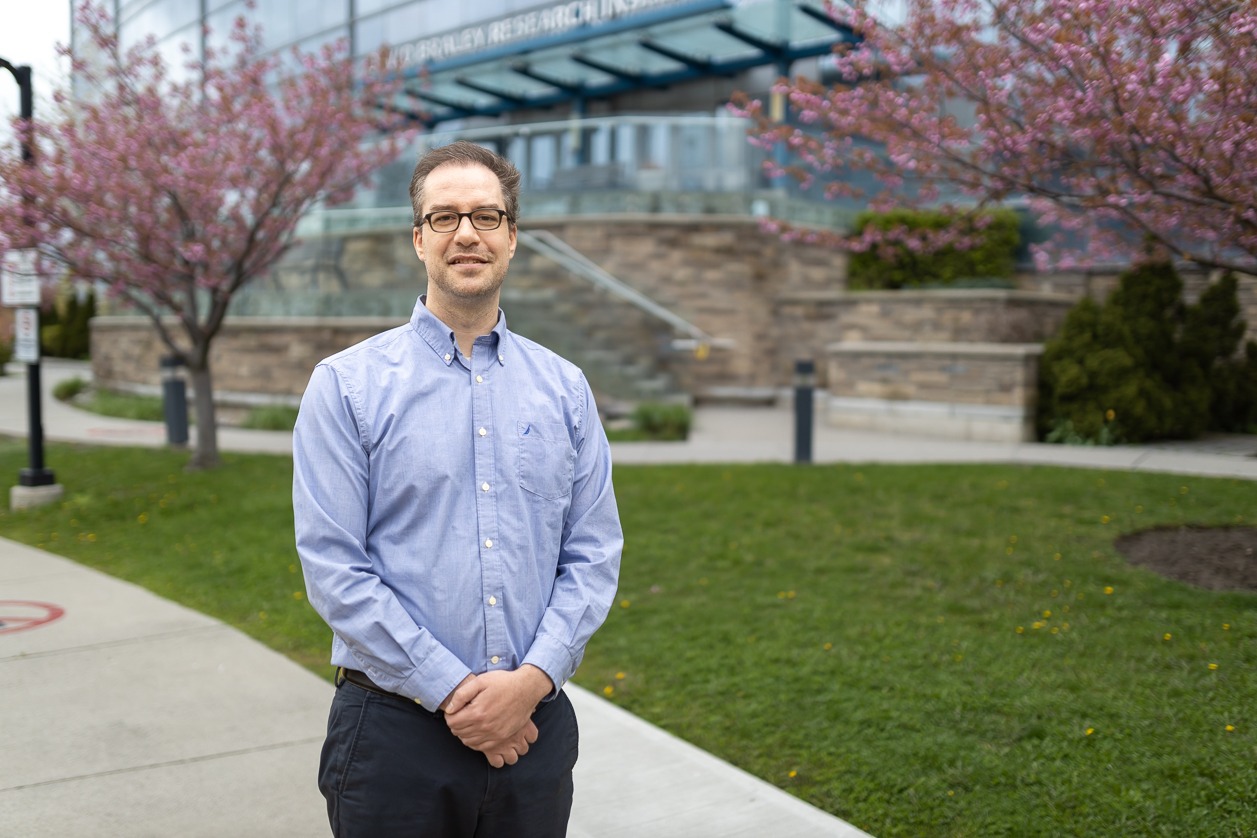

Dr. Peter Gross, a Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) thrombosis physician, was interested in seeing the blood-clotting process with his own eyes using a microscope. So he developed tools that identify the activity of thrombin — a clotting enzyme in the blood – allowing him to visually witness blood clotting. This also works with a finger-prick of blood under fluorescent lighting.

Gross was one of four researchers honoured at the Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation’s Gala last month celebrating research and innovation at HHS. Each of the recipients — which also included Drs. Jason Roberts, Guillaume Paré and Mark Tarnopolsky — received a $40,000 grant to take their innovative commercialization research projects to the next level.

With this support, Gross and his team have launched a study to prove that testing the blood with a specific device can accurately show that people properly stopped blood thinners before surgery.

“Getting the handheld device has really made a difference in our ability to expand testing.”

If this study shows positive results, the team could also explore using this device with stroke patients in the emergency department to determine whether or not there are blood thinners in the patient’s system to guide treatment options.

“There are many applications for this device to help guide patient care,” says Gross. “We’re also working with a team in Toronto to see if it can be used during complex surgeries to help determine which medications and blood products are needed.”

Widening their research scope

For patients with a blood-clotting disorder like hemophilia, measuring thrombin in a finger-prick of their blood can help advise their daily treatment regimen for managing this condition. Gross and his team at the Thrombosis & Atherosclerosis Research Institute (TaARI), of HHS and McMaster University found a device that can do just that. They’re also testing if it can be used to accurately diagnose hemophilia in Third World countries so that treatment can be made available to those who need it.

Meanwhile, the team has found another use for the device — point-of-care testing for cardiac surgery patients to help support decisions around blood transfusions.

Many people with heart conditions take blood-thinning medication, which prevents their blood from clotting. However, they must stop taking these blood thinners when having surgery. By testing their blood prior to surgery with this finger-prick test, the patient’s care team can be confident that the thinner has cleared, and are not at risk for bleeding.

“Since we don’t currently test patients’ blood before surgery, we don’t actually know if there are still blood thinners in the patient’s system,” says Gross. “This impacts the risk of bleeding and may affect the amount of blood that’s needed to be transfused during the surgery.”

Pandemic-driven advancement

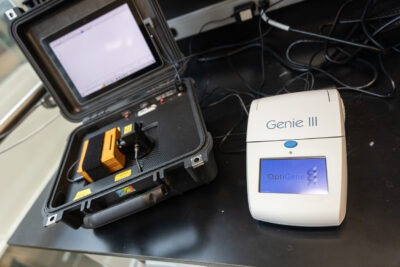

The suitcase-style device on the left was the only one Gross could find that utilized the technology needed for his project. Until the pandemic hit and the smaller, simpler device on the right was created, originally for COVID testing.

While the testing itself is promising, having an easy-to-use handheld device also makes a difference in its functionality. This wasn’t always the case. Gross started the original project with hemophilia patients prior to the pandemic. At the time, finding a device that already used the fluorescent lighting needed to identify thrombin meant using a large suitcase-style kit that was originally designed for marine biology testing. While it worked, it wasn’t user-friendly.

However, for Gross, a silver lining of the pandemic was the availability of a handheld COVID testing device that also used fluorescent lighting. Since it already went through all regulatory approvals, it became the ideal device to use for identifying thrombin in the blood.

“The old device just wasn’t ideal to work with, and we weren’t in a position to make our own,” says Gross. “Getting the handheld device has really made a difference in our ability to expand testing.”