Preemie doctor Saroj Saigal celebrates 50 years at HHS

When Dr. Saroj Saigal began her career as a neonatologist in the early 1970s, caring for the tiniest premature infants was a fairly new medical specialty. At the time, there were just a handful of neonatal intensive care units (NICU) in Canada. After her training at McGill University, Saigal became aware of some forward-thinking plans for a new Regional Referral Tertiary Care Perinatal Unit in Hamilton, pioneered by neonatologist Dr. Jack Sinclair and McMaster University’s Chair of Pediatrics, Dr. Alvin Zipursky, so she decided to start her career here.

“Over the past 50 years, no other field has made such significant advancements in the survival and care of patients than neonatology.”

Fifty years later, she is still with Hamilton Health Sciences, caring for premature babies at McMaster Children’s Hospital, conducting research and making a difference in the lives of thousands of families.

“HHS is so proud to have had Dr. Saigal with our organization for 50 years,” says Rob MacIsaac, President and CEO, Hamilton Health Sciences. “She has had a successful career here and is a true inspiration.”

Looking back

While Saigal has always worked with premature babies, the landscape has changed drastically. She started her career in what she describes as an exciting yet challenging time.

While witnessing the evolution of the field over the years she played a part in its path, though she says it was a small part. The biggest change in Hamilton’s healthcare scene was not just the amalgamation of hospitals, but also the creation of a regional children’s hospital for specialized care.

“Back in the 70s there were specialists in each field at each hospital so there was some initial reluctance to the concept of amalgamation,” she says. Saigal herself worked in the maternity unit at the former Henderson Hospital, now the Juravinski Hospital. “On top of that, for specialized maternal-infant care, many physicians in the region referred patients to Toronto because Hamilton wasn’t on the map yet for healthcare.”

Dr. Saigal (in the centre of the photo behind the incubator) was part of the NICU and Perinatal Unit team when it first opened in 1973 at McMaster Children’s Hospital.

When the NICU and regional Perinatal Unit first opened in 1973 at McMaster Hospital, it was not yet exclusively a pediatric hospital. However, all care for premature infants in Hamilton moved to that location, as did all specialists. So, Saigal relocated to what is now McMaster Children’s Hospital.

It was the first time that high-risk mothers and premature infants were treated as one unit. These individuals were transferred to the Perinatal Unit to give birth, instead of the baby being transferred after birth, thus improving their survival. Another first was the all-day open visiting hours for all family members. These were just some of the new concepts that were implemented to ensure the best possible outcome for premature infants to survive and thrive.

While Saigal wasn’t part of the planning of this innovative NICU and says she was just in the right place at the right time, she did contribute to advancing the care for these tiny early patients. Within a decade, the neonatal division was recognized on a global scale.

Creating follow-up care after the NICU

Neonatal intensive care started in the late 1960s and survival of the tiny infants was barely 10%. By the late 1970s, the survival rate of premature babies weighing less than 2 pounds at birth was only 40%. Around a quarter of those who survived had disabilities such as cerebral palsy, cognitive deficits and blindness.

“Back then, no one knew the long-term impact of surviving and what the quality of life would be for these individuals as they grew,” says Saigal.

In addition to caring for infants in the NICU, she was assigned to organize “follow-up” care after the babies were discharged from the NICU.

Despite Saigal not having a background in this type of care and having very few of these programs in Canada, she developed the program from scratch. She determined the frequency of appointments, created resources for parents, helped with physical and cognitive issues and began collecting data. She was later joined by Dr. Peter Rosenbaum, a developmental pediatrician, and they’ve been working together ever since.

Dr. Saroj Saigal presented the first poster on the outcome of premature infants with a birthweight of less than 1000 grams (two pounds) in 1983 at the Society of Pediatric Research in Washington DC.

“We wanted to know what happens once these infants went home. What was their quality of life and could we determine how to prevent common medical and developmental issues in the future,” she says.

That curiosity paid off. Saigal’s work and research, along with other leaders in the field, did lead to better health for her patients. Today, the survival rate of premature babies weighing less than 2 pounds has more than doubled to over 85%. The disability rates have not increased despite the survival of extremely immature infants of 23 to 24 weeks gestation. Cerebral palsy rates are falling and blindness now occurs in less than 2% of preemies.

“I learned just how resilient kids can be.”

This program has expanded over the years and is now located in the 2G clinic at McMaster Children’s Hospital. It’s for patients born at 29 weeks or less, weighing less than 1500 grams (3.3 pounds) or having other serious health issues.

Saigal and Rosenbaum ran the clinic by themselves for several decades, but now there’s a multi-disciplinary team of physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, a psychometrician, dietitian, nurse practitioner and an additional developmental pediatrician to help premature children achieve their best potential. Even during the pandemic, the clinic has been running remotely to continue to support children and their families.

50 years of life-changing care and counting

While Saigal continued to participate in clinical care in the outpatient follow-up program, she also continued her research. She followed a cohort of premature infants born in the late 70s and early 80s from birth into their 40s.

Earlier reports focused on their medical outcomes, school achievements, employment and independent living, but she eventually explored patients’ perspectives on their quality of life.

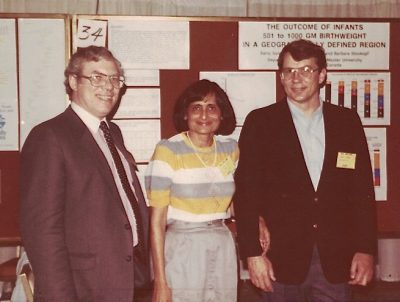

Dr. Saroj Saigal with Dr. Jack Sinclair, one of the founders of the MCH NICU, and a mentor to Saigal.

“I learned a lot from the parents and children,” she says. “One thing being that as doctors, we have a different perception on the quality of life of our patients. We expected theirs to be lower since many had physical and developmental disabilities. But that wasn’t the case. I learned just how resilient kids can be.”

A few years ago during her most recent touchpoint with “the children,” as she still calls them, even though they’re in their 40s, she asked them to write about what their lives were like knowing that they were some of the smallest babies to survive at the time. She was so touched by their words and self-reflection that she compiled them into a self-published book, supported by McMaster University’s Department of Pediatrics, called Preemie Voices, with an accompanying video documentary.

Another more recent accomplishment for Saigal is developing partnerships with neonatal centres around the world to share data. Since the data being collected is on the tiniest of premature babies, it represents a very small percentage of infants born at each site. Individually, it takes a long time for each centre to collect enough data to complete a study. By sharing data, it has already resulted in the release of many publications with a large sample size on the health of premature babies worldwide. This means advancing their care more effectively and efficiently.

Saigal is internationally recognized for her studies that focus on the quality of life and consequences of having been born extremely premature. She says she enjoys participating in the follow-up clinic and has no plans to retire anytime soon.

“Over the past 50 years, no other field has made such significant advancements in the survival and care of patients than neonatology,” she says. “It has been an exciting and rewarding journey and there’s still so much to learn.”