Banking on patient donations for leading-edge leukemia research

Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS) hematologist Dr. Tobias Berg is passionate about translational research, where discoveries in the lab lead to treatments that prolong and save lives. Berg leads a research team dedicated to improving outcomes for people diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a rare type of cancer that starts in the blood-forming cells of the bone marrow.

“We’re very open to collaborating locally, provincially, nationally and internationally.” — Dr. Tobias Berg.

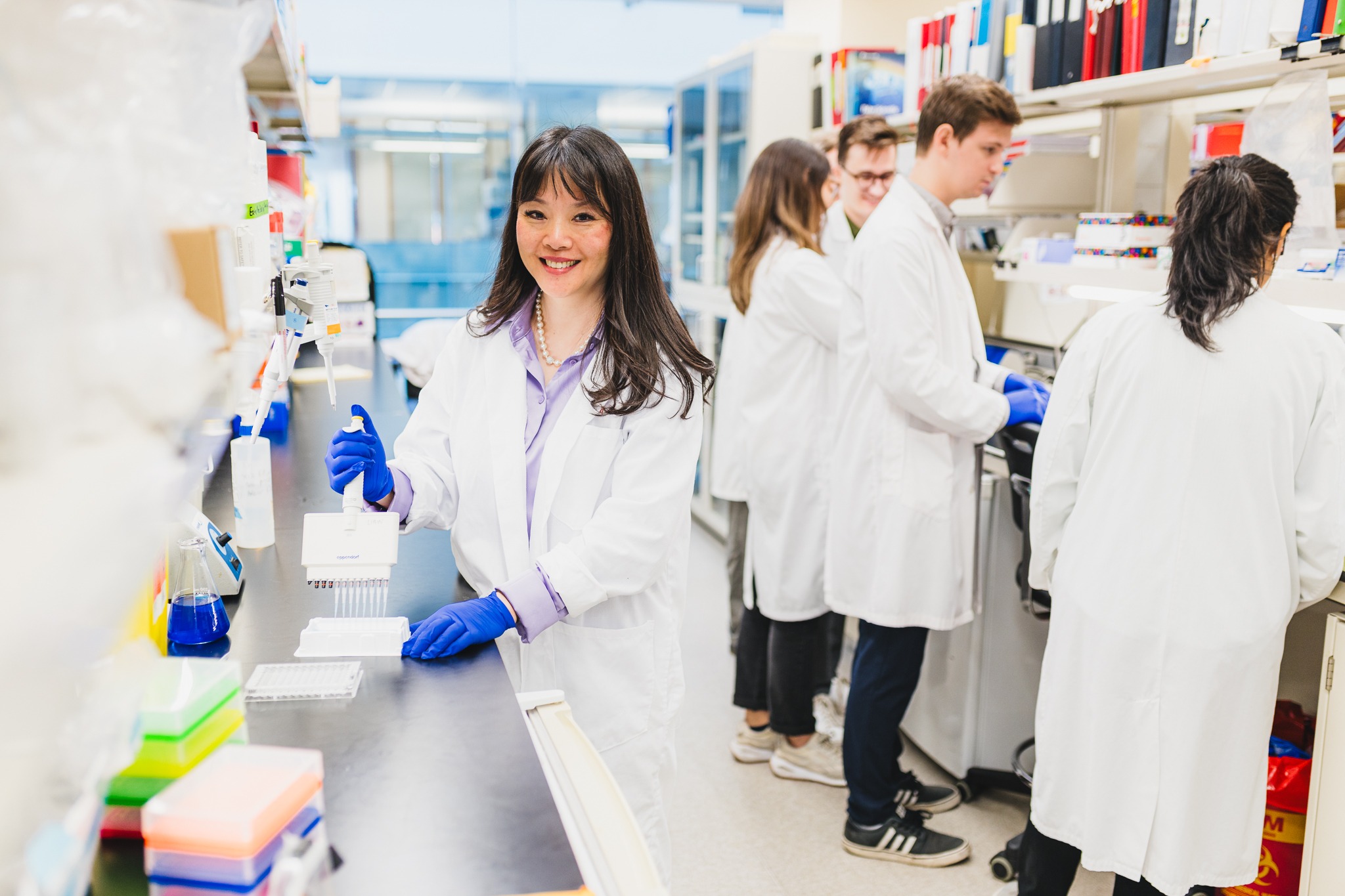

Vital supporters of this leading-edge research include hundreds of HHS blood cancer patients, including many with AML and multiple myeloma, who volunteer to provide cell samples to the HHS McMaster Cancer Research Stem Cell Bank.

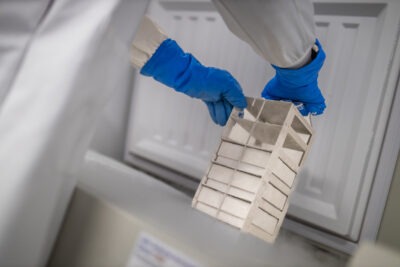

AML samples from patients are stored in a special freezer at very low temperatures (-150 °C).

Samples are taken during medical procedures related to their care, such as blood being drawn or bone marrow biopsies.

“Patients undergoing certain procedures as part of their care plan may be asked if they would be willing to have a small part of their sample go towards research,” says Berg. “So no additional procedure is needed in order to collect samples.”

The cell bank currently collects approximately 100 samples per year, from over 50 patients per year. Most patients are keen to donate. “In fact, I’ve rarely experienced anyone saying no,” says Berg. “It’s very important to these patients that they have opportunities to contribute to advancements through research that could prolong future patients’ lives.”

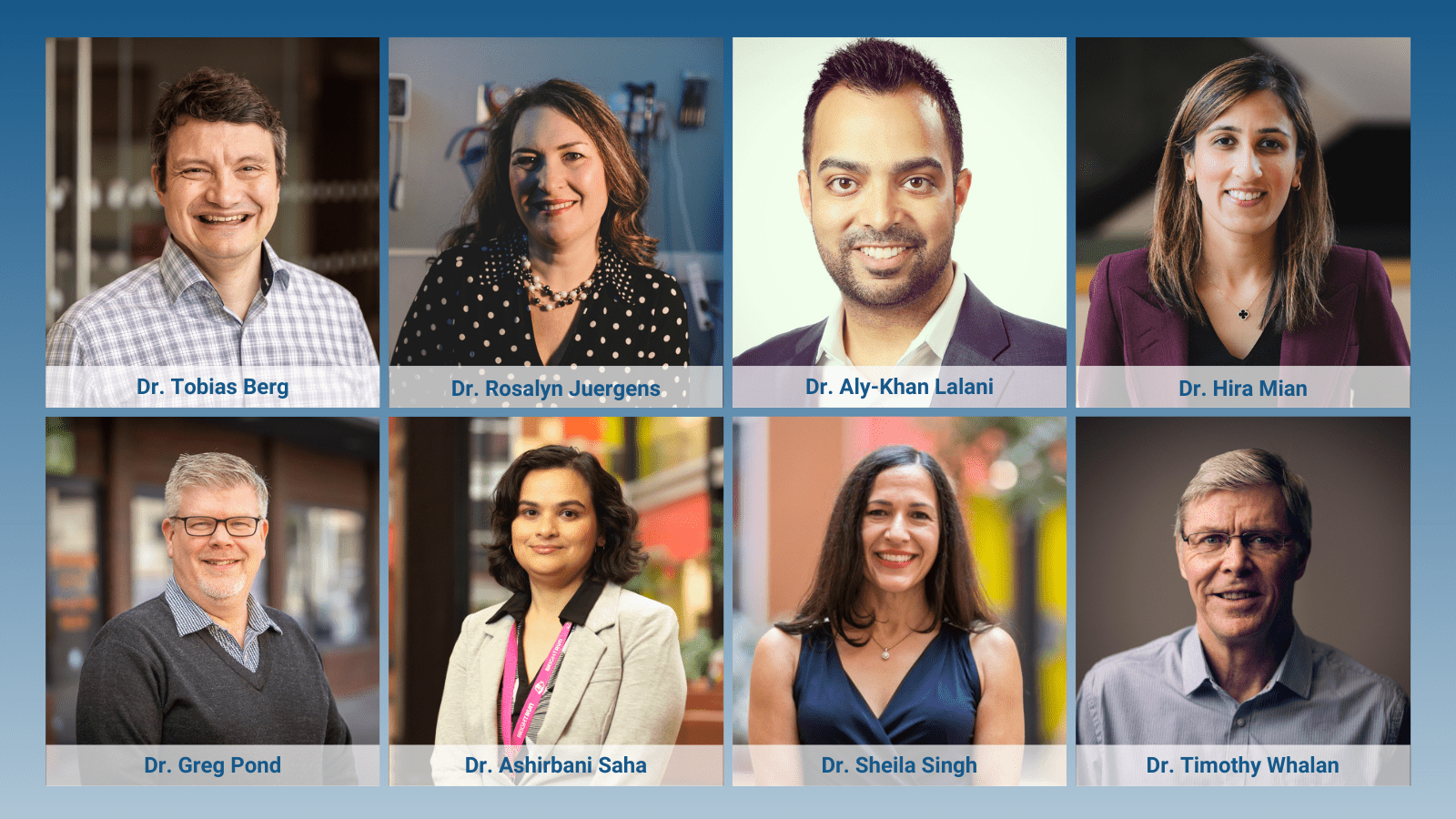

“Dr. Berg is an outstanding researcher and a caring physician whose leadership is improving outcomes for cancer patients.” — Dr. Marc Jeschke, HHS vice president of research and chief scientific officer.

Berg spends half his work week leading research into AML at the Berg Research Lab at the Centre for Discovery in Cancer Research at McMaster University, where he is senior scientist and leads the translational oncology program. This program acts as a bridge between basic scientists and clinicians working to improve the lives of patients affected by cancer. He’s also a scientist with the Escarpment Cancer Research Institute (ECRI), a joint institute of HHS and McMaster University. Based at HHS Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre, ECRI’s work focuses on research that has an impact on patient outcomes.

The other half of Berg’s time is spent caring for patients as a hematologist at HHS Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre.

Berg started expanding the existing cell bank after arriving in Hamilton from Germany in 2019, as the inaugural Boris Family Chair in Leukemia and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Translational Research at McMaster.

“Dr. Berg is an outstanding researcher and a caring physician whose leadership is improving outcomes for cancer patients,” says Dr. Marc Jeschke, vice president of research and chief scientific officer for HHS. “Dr. Berg has also been instrumental supporting leading-edge research through his commitment to expanding the cell bank.”

Many diseases in one cancer

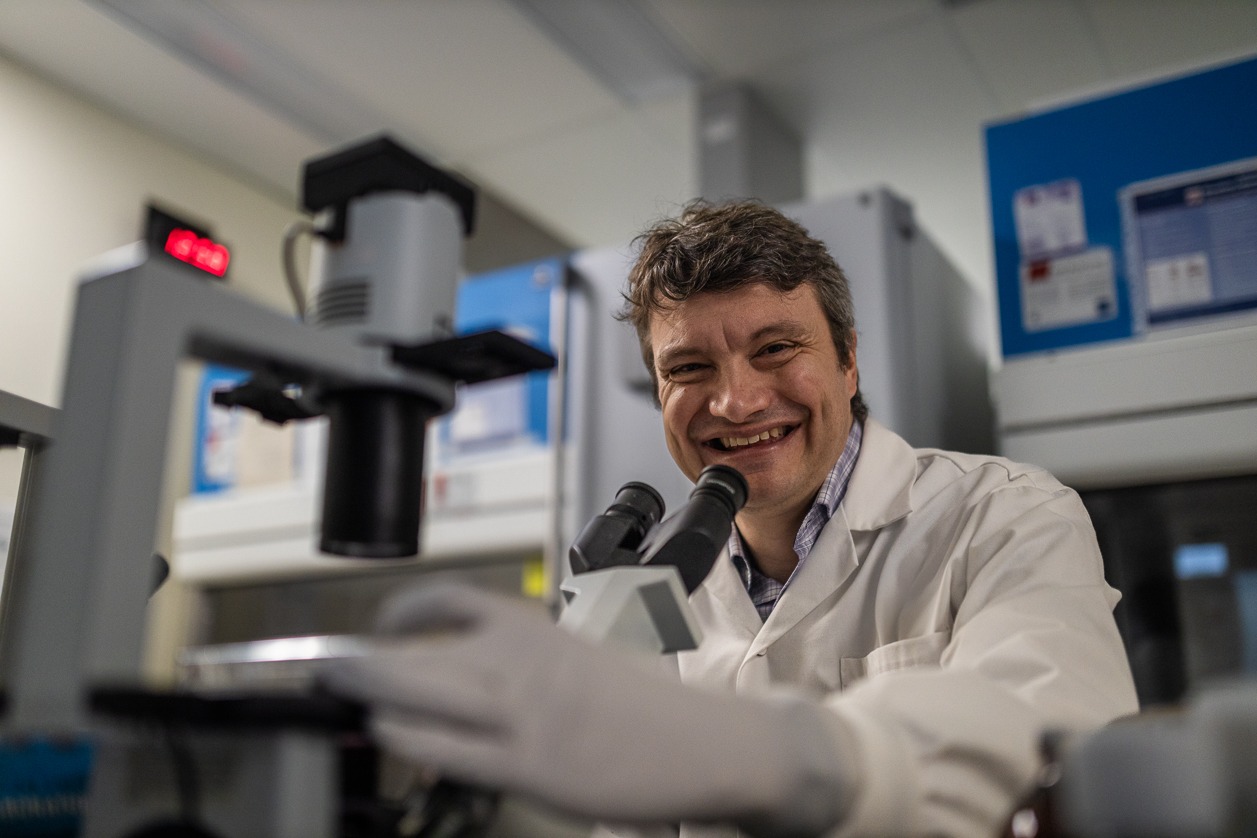

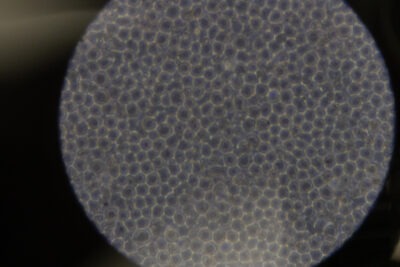

AML cells under the microscope.

While AML is a rare cancer, it’s the most common type of acute leukemia in adults. The most effective treatment, which offers a potential cure, is an allogeneic stem cell transplant where the patient receives stem cells from a donor. Even with a transplant, relapse is unfortunately common. Due to certain pre-existing conditions, not all AML patients qualify for a transplant which leads to a less than 30 per cent chance of long-term survival with this disease.

That’s why research into prolonging patients’ lives is so vital.

Improving outcomes

While AML is considered one type of cancer, it’s actually many different diseases because patients have fairly unique combinations of mutations that occur and drive the disease.

“So it’s important to understand, through research, the biology of these subgroups and mutations in order discover the most appropriate treatment for every individual patient,” says Berg, who analyses the metabolism of diseased cells and how they interact with the immune system in order to understand why relapse is so common and find more effective treatments for managing care after a transplant to prevent a reoccurrence.

One starting point is how to deal with minimal residual disease, which refers to a small number of cancer cells often left in the body after cancer treatment, such as a stem cell transplant. Researchers try and determine why these cells can survive treatment, and why they may even continue to grow and mutate after treatment, causing a relapse.

“In order to better treat minimal residual disease, we need to understand how leukemia cells become resistant to treatment,” says Berg.

Where do leukemia cells get their energy?

“We do this by analyzing the metabolism of diseased cells and how they interact with the immune system,” he says. “We look at where leukemia cells derive their energy from and see how our treatments change this process. Since relapse after a transplant often happens when diseased cells become invisible for the immune system, we also try to understand how they get recognized by the immune system. As the donor’s immune system is a key part of the transplant, we study how we can improve the way the immune system can recognize the leukemia cells.”

Berg and his team are initiating a novel approach to understand how genes are regulated on a single-cell level. “We are doing these single cell studies with a new technology we got running with funding from the Marta and Owen Boris Foundation,” says Berg, adding he’s grateful for ongoing support from the foundation, without which none of this research would be possible, as well as funding from other organizations including the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and the Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation.

Berg recently also received funding from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of Canada to explore how healthy cells surrounding cancerous ones contribute to resistance of the diseased cells, and which treatments this could be blocked with. “We are particularly interested in changes in the cancerous cells’ energy production that occur due to this interaction with surrounding cells,” says Berg.

Opportunities for collaboration

While Berg’s team focuses on AML, they are far from siloed in their research. “Working at the Centre for Discovery in Cancer Research allows for collaboration with other researchers focused on other types of cancer and allows us to work together with outstanding researchers in the fields of immunology, stem cell biology and metabolism,” says Berg.

“We share our experiences, research technologies, and collaborate on ways to improve outcomes for patients with a variety of cancers. Our work recently, for example, helped to better understand the effect of a novel experimental approach in prostate and lung cancer. We’re very open to collaborating locally, provincially, nationally and internationally.”

April is Cancer Awareness Month in Canada, a time to recognize our researchers, health care practitioners, volunteers, caregivers, policymakers, and community members who continue to innovate and advance cancer research and care across the country.

Cancer remains the leading cause of death in Canada. Today, there are 1.5 million Canadians living with and beyond cancer.