Eating disorders team makes hospital feel like home

Mind Over Matter: Inside the Shadow Pandemic of Pediatric Eating Disorders

The pandemic has thrown many young people into crisis. Prolonged periods of social isolation, disconnection from regular routines and in many cases, a new normal for family dynamics is resulting in the growth of increasingly unbalanced, unhealthy, concerning and dangerous habits.

The nationally recognized Pediatric Eating Disorders program at McMaster Children’s Hospital is seeing an unprecedented number of children and youth coming to the hospital with serious mental and physical health concerns; a trend that is anticipated to continue into the future.

This is the final piece in a three-part series shining a light on the eating disorder diagnosis and its treatment from three different and unique perspectives: the provider, the patient and parent, and the program administration.

Part 3: Eating disorders team makes hospital feel like home

Running a busy, high-volume clinical program can sometimes feel like running on a treadmill. The longer you’re on it, the harder you have to work to achieve the same result. At times, it can feel like you’re not moving forward.

Regardless, you keep on going for your patients.

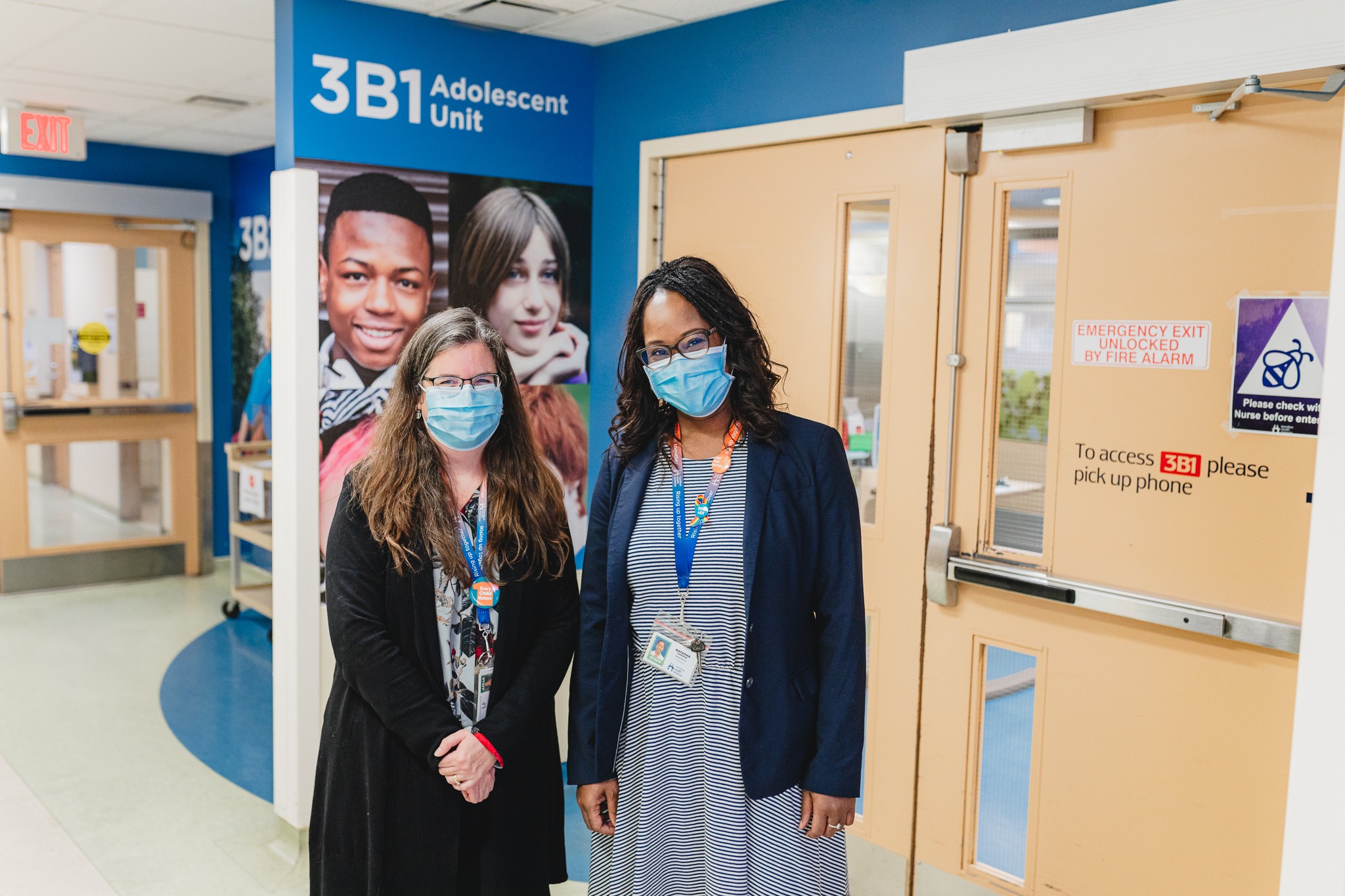

Jen Hoppe, interim clinical manager of the eating disorders program at Hamilton Health Sciences’ McMaster Children’s Hospital (MCH) knows the feeling. Throughout the pandemic, the program has been inundated with referrals for young people needing care.

“It’s definitely been a challenge for the team,” says Hoppe. “Not only are we seeing increased number of patients, we are also seeing increased level of severity in the patients requiring service.”

The increase in youth needing care for eating disorders has been referred to as a “shadow pandemic” existing in parallel to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eating disorders unit

Program needing to pivot

The MCH program operates a six-bed inpatient unit providing long-term intensive interventions, a day hospital program for medically stable youth who need nutrition supervision, and outpatient services to patients with varying levels of severity. Each of the three areas has been impacted by the pandemic.

“We’ve been consistently operating eight beds in our unit to help keep up with demand. We’re only funded to operate six. That means we need to pull in additional staff and resources to make sure every young person in our care gets what they need,” says Hoppe.

Sometimes, patients get admitted to a bed in a different unit since there isn’t enough space, and staff resources are provided to the units so that the patients still have access to the same specialized care. This was not unheard of before the pandemic, but has since become more commonplace, even with the addition of two more beds.

The day hospital program has also pivoted over the past 18 months. The program was closed for the first part of the pandemic, then brought back in a virtual setting until fall 2021 when patients started returning to the unit in person.

Staff on the unit work at full capacity to provide care and keep patients and their families safe.

More demand than ever

Staffing on the care team includes pediatricians, a psychiatrist, nursing, dietary, social work, psychology, child and youth counselors, and child life staff to name a few.

“We do everything we can for our patients and their families,” Hoppe says. “My job is to make sure we have staff who can work at full capacity to provide care and keep patients and their families safe. Staff need to feel supported in their roles. We live in a new world order of COVID restrictions and keeping morale up is important, but can obviously be challenging in these uncertain and demanding times.”

Referrals to the program during the pandemic are up about 90 per cent and admissions are up more than 50 per cent compared to pre-pandemic levels. Outpatient services for medically stable patients have waitlists pushing upwards of two years.

The care team is feeling it, but remain committed to their work.

“We have very dedicated, very skilled staff who chose well before the pandemic to be dedicated to this work. That hasn’t changed. We do it because we know this is what we have to do, and we want to do it,” she continues.

Funding on its way

After months of advocacy and discussion to help the Ontario government understand the program’s challenges, the province recently announced additional funding for eating disorders programs at MCH and across Ontario. Details are still being finalized, but it’s welcome news for the team and their patients.

Bruce Squires

“I cannot overstate how important this funding is for patient care,” says MCH president Bruce Squires. “All credit is due to our care team who made it work through a very tough time, making sure patients always got what they need. We definitely appreciate this commitment from the province and their recognition of our team.”

Squires and the heads of other children’s hospitals and health centres led a unified effort to meet with government and explain the dire need for extra support. But that wasn’t the only advocacy at play.

“Patients and their families are the most wonderful advocates. They know the impact a diagnosis can have on their child and family, and they know how important it is to be able to get great care when they need it. I believe the government definitely heard families on this one,” he says.

Making the hospital feel like home

As soon as possible, the team is going to take a minute to catch its breath and figure out how to get the biggest bang for these operational bucks. The goal is to immediately start reducing the waitlist, while making sure staff have what they need to restore balance to their working lives.

“As a program leader, I need to make sure we have people in place to provide the care, as well as make sure our hospital is a safe, welcoming place for families and patients,” says Hoppe. “On our unit, the hospital can become the patient’s home for weeks on end. We need to be sure that it’s the best possible place to help them get well.”